Please Avoid detectCores() in your R Packages

The detectCores() function of the parallel package is probably

one of the most used functions when it comes to setting the number of

parallel workers to use in R. In this blog post, I’ll try to explain

why using it is not always a good idea. Already now, I am going to

make a bold request and ask you to:

Please avoid using

parallel::detectCores()in your package!

By reading this blog post, I hope you become more aware of the

different problems that arise from using detectCores() and how they

might affect you and the users of your code.

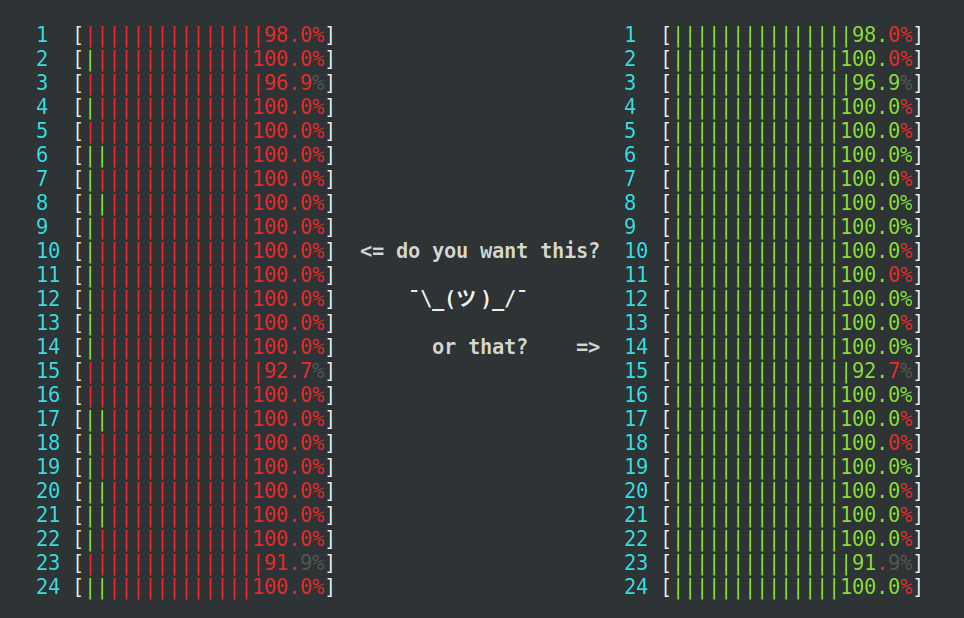

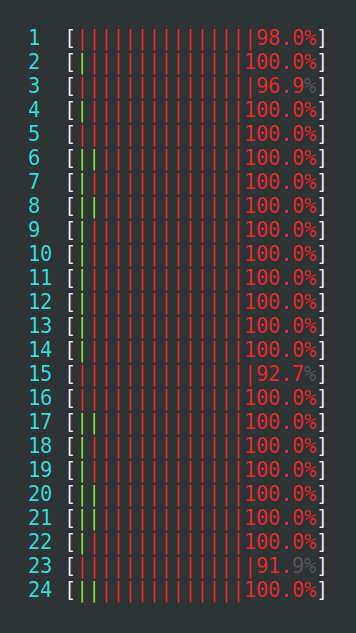

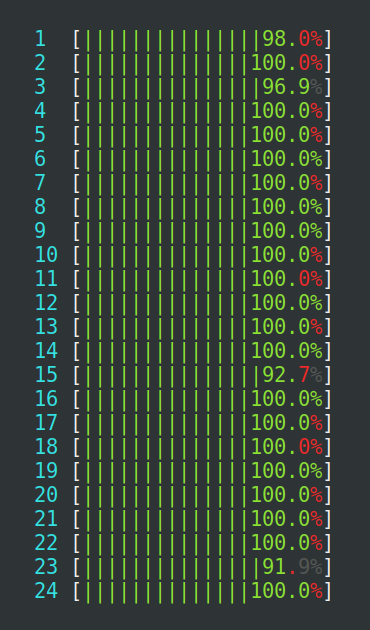

detectCores() risks overloading the

machine where R runs, even more so if there are other things already

running. The machine seen at the left is heavily loaded, because too

many parallel processes compete for the 24 CPU cores available, which

results in an extensive amount of kernel context switching (red),

which wastes precious CPU cycles. The machine to the right is

near-perfectly loaded at 100%, where none of the processes use more

than they may use (mostly green).

TL;DR

If you don’t have time to read everything, but will take my word that

we should avoid detectCores(), then the quick summary is that you

basically have two choices for the number of parallel workers to use

by default;

Have your code run with a single core by default (i.e. sequentially), or

replace all

parallel::detectCores()withparallelly::availableCores().

I’m in the conservative camp and recommend the first alternative. Using sequential processing by default, where the user has to make an explicit choice to run in parallel, significantly lowers the risk for clogging up the CPUs (left panel in Figure 1), especially when there are other things running on the same machine.

The second alternative is useful if you’re not ready to make the move

to run sequentially by default. The availableCores() function of

the parallelly package is fully backward compatible with

detectCores(), while it avoids the most common problems that comes

with detectCores(), plus it is agile to a lot more CPU-related

settings, including settings that the end-user, the systems

administrator, job schedulers and Linux containers control. It is

designed to take care of common overuse issues so that you do not have

to spend time worry about them.

Background

There are several problems with using detectCores() from the

parallel package for deciding how many parallel workers to use.

But before we get there, I want you to know that we find this function

commonly used in R script and R packages, and frequently suggested in

tutorials. So, do not feel ashamed if you use it.

If we scan the code of the R packages on CRAN (e.g. by searching

GitHub1), or on Bioconductor (e.g. by searching

Bioc::CodeSearch) we find many cases where detectCores() is used.

Here are some variants we see in the wild:

cl <- makeCluster(detectCores())

cl <- makeCluster(detectCores() - 1)

y <- mclapply(..., mc.cores = detectCores())

registerDoParallel(detectCores())

We also find functions that let the user choose the number of workers

via some argument, which defaults to detectCores(). Sometimes the

default is explicit, as in:

fast_fcn <- function(x, ncores = parallel::detectCores()) {

if (ncores > 1) {

cl <- makeCluster(ncores)

...

}

}

and sometimes it’s implicit, as in:

fast_fcn <- function(x, ncores = NULL) {

if (is.null(ncores))

ncores <- parallel::detectCores() - 1

if (ncores > 1) {

cl <- makeCluster(ncores)

...

}

}

As we will see next, all the above examples are potentially buggy and might result in run-time errors.

Common mistakes when using detectCores()

Issue 1: detectCores() may return a missing value

A small, but important detail about detectCores() that is often

missed is the following section in help("detectCores", package =

"parallel"):

Value

An integer, NA if the answer is unknown.

Because of this, we cannot rely on:

ncores <- detectCores()

to always work, i.e. we might end up with errors like:

ncores <- detectCores()

workers <- parallel::makeCluster(ncores)

Error in makePSOCKcluster(names = spec, ...) :

numeric 'names' must be >= 1

We need to account for this, especially as package developers. One way to handle it is simply by using:

ncores <- detectCores()

if (is.na(ncores)) ncores <- 1L

or, by using the following shorter, but also harder to understand, one-liner:

ncores <- max(1L, detectCores(), na.rm = TRUE)

This construct is guaranteed to always return at least one core.

Shameless advertisement for the parallelly package: In

contrast to detectCores(), parallelly::availableCores() handles

the above case automatically, and it guarantees to always return at

least one core.

Issue 2: detectCores() may return one

Although it’s rare to run into hardware with single-core CPUs these days, you might run into a virtual machine (VM) configured to have a single core. Because of this, you cannot reliably use:

ncores <- detectCores() - 1L

or

ncores <- detectCores() - 2L

in your code. If you use these constructs, a user of your code might

end up with zero or a negative number of cores here, which another way

we can end up with an error downstream. A real-world example of this

problem can be found in continous integration (CI) services,

e.g. detectCores() returns 2 in GitHub Actions jobs. So, we need to

account also for this case, which we can do by using the above

max() solution, e.g.

ncores <- max(1L, detectCores() - 2L, na.rm = TRUE)

This is guaranteed to always return at least one.

Shameless advertisement for the parallelly package: In

contrast, parallelly::availableCores() handles this case via

argument omit, which makes it easier to understand the code, e.g.

ncores <- availableCores(omit = 2)

This construct is guaranteed to return at least one core, e.g. if

there are one, two, or three CPU cores on this machine, ncores will

be one in all three cases.

Issue 3: detectCores() may return too many cores

When we use PSOCK, SOCK, or MPI clusters as defined by the

parallel package, the communication between the main R session and

the parallel workers is done via R socket connection. Low-level

functions parallel::makeCluster(), parallelly::makeClusterPSOCK(),

and legacy snow::makeCluster() create these types of clusters. In

turn, there are higher-level functions that rely on these low-level

functions, e.g. doParallel::registerDoParallel() uses

parallel::makeCluster() if you are on MS Windows,

BiocParallel::SnowParam() uses snow::makeCluster(), and

plan(multisession) and plan(cluster) of the future package

uses parallelly::makeClusterPSOCK().

R has a limit in the number of connections it can have open at any

time. As of R 4.2.2, the limit is 125 open connections. Because of

this, we can use at most 125 parallel PSOCK, SOCK, or MPI workers. In

practice, this limit is lower, because some connections may already be

in use elsewhere. To find the current number of free connections, we

can use parallelly::freeConnections(). If we try to launch a

cluster with too many workers, there will not be enough connections

available for the communication and the setup of the cluster will

fail. For example, a user running on a 192-core machine will get

errors such as:

> cl <- parallel::makeCluster(detectCores())

Error in socketAccept(socket = socket, blocking = TRUE, open = "a+b", :

all connections are in use

and

> cl <- parallelly::makeClusterPSOCK(detectCores())

Error: Cannot create 192 parallel PSOCK nodes. Each node needs

one connection, but there are only 124 connections left out of

the maximum 128 available on this R installation

Thus, if we use detectCores(), our R code will not work on larger,

modern machines. This is a problem that will become more and more

common as more users get access to more powerful computers.

Hopefully, R will increase this connection limit in a future release,

but until then, you as the developer are responsible to handle also

this case. To make your code agile to this limit, also if R increases

it, you can use:

ncores <- max(1L, detectCores(), na.rm = TRUE)

ncores <- min(parallelly::freeConnections(), ncores)

This is guaranteed to return at least zero (sic!) and never more than what is required to create a PSOCK, SOCK, and MPI cluster with than many parallel workers.

Shameless advertisement for the parallelly package: In the

upcoming parallelly 1.33.0 version, you can use

parallelly::availableCores(constraints = "connections") to limit

the result to the current number of available R connections. In

addition, you can control the maximum number of cores that

availableCores() returns by setting R option

parallelly.availableCores.system, or environment variable

R_PARALLELLY_AVAILABLECORES_SYSTEM,

e.g. R_PARALLELLY_AVAILABLECORES_SYSTEM=120.

Issue 4: detectCores() does not give the number of “allowed” cores

There’s a note in help("detectCores", package = "parallel") that

touches on the above problems, but also on other important limitations

that we should know of:

Note

This [=

detectCores()] is not suitable for use directly for themc.coresargument ofmclapplynor specifying the number of cores inmakeCluster. First because it may returnNA, second because it does not give the number of allowed cores, and third because on Sparc Solaris and some Windows boxes it is not reasonable to try to use all the logical CPUs at once.

When is this relevant? The answer is: Always! This is because as package developers, we cannot really know when this occurs, because we never know on what type of hardware and system our code will run. So, we have to account for these unknowns too.

Let’s look at some real-world case where using detectCores() can

become a real issue.

4a. A personal computer

A user might want to run other software tools at the same time while running the R analysis. A very common pattern we find in R code is to save one core for other purposes, say, browsing the web, e.g.

ncores <- detectCores() - 1L

This is a good start. It is the first step toward your software tool acknowledging that there might be other things running on the same machine. However, contrary to end-users, we as package developers cannot know how many cores the user needs, or wishes, to set aside. Because of this, it is better to let the user make this decision.

A related scenario is when the user wants to run two concurrent R

sessions on the same machine, both using your code. If your code

assumes it can use all cores on the machine (i.e. detectCores()

cores), the user will end up running the machine at 200% of its

capacity. Whenever we use over 100% of the available CPU resources,

we get penalized and waste our computational cycles on overhead from

context switching, sub-optimal memory access, and more. This is where

we end up with the situation illustrated in the left part of

Figure 1.

Note also that users might not know that they use an R function that runs on all cores by default. They might not even be aware that this is a problem. Now, imagine if the user runs three or four such R sessions, resulting in a 300-400% CPU load. This is when things start to run slowly. The computer will be sluggish, maybe unresponsive, and mostly likely going to get very hot (“we’re frying the computer”). By the time the four concurrent R processes complete, the user might have been able to finish six to eight similar processes if they would not have been fighting each other for the limited CPU resources.

4b. A shared computer

In the academia and the industry, it is common that several users share the same compute server och set of compute nodes. It might be as simple as they SSH into a shared machine with many cores and large amounts of memory to run their analysis there. On such setups, load balancing between users is often based on an honor system, where each user checks how many resources are available before launching an analysis. This helps to make sure they don’t end up using too many cores, or too much memory, slowing down the computer for everyone else.

Now, imagine they run a software tool that uses all CPU cores by

default. In that case, there is a significant risk they will step on

the other users’ processes, slowing everything down for everyone,

especially if there is already a big load on the machine. From my

experience in academia, this happens frequently. The user causing the

problem is often not aware, because they just launch the problematic

software with the default settings, leave it running, with a plan to

coming back to it a few hours or a few days later. In the meantime,

other users might wonder why their command-line prompts become

sluggish or even non-responsive, and their analyses suddenly take

forever to complete. Eventually, someone or something alerts the

systems administrators to the problem, who end up having to drop

everything else and start troubleshooting. This often results in them

terminating the wild-running processes and reaching out to the user

who runs the problematic software, which leads to a large amount of

time and resources being wasted among users and administrators. All

this is only because we designed our R package to use all cores by

default. This is not a made-up toy story; it is a very likely

scenario that happens on shared servers if you make detectCores()

the default in your R code.

Shameless advertisement for the parallelly package: In

contrast to detectCores(), if you use parallelly::availableCores()

the user, or the systems administrator, can limit the default number

of CPU cores returned by setting environment variable

R_PARALLELLY_AVAILABLECORES_FALLBACK. For instance, by setting it

to R_PARALLELLY_AVAILABLECORES_FALLBACK=2 centrally,

availableCores() will, unless there are other settings that allow

the process to use more, return two cores regardless how many CPU

cores the machine has. This will lower the damage any single process

can inflict on the system. It will take many such processes running

at the same time in order for them to have an overall a negative

impact. The risk for that to happen by mistake is much lower than

when using detectCores() by default.

4c. A shared compute cluster with many machines

Other, larger compute systems, often referred to as high-performance

compute (HPC) cluster, have a job scheduler for running scripts in

batches distributed across multiple machines. When users submit their

scripts to the scheduler’s job queue, they request how many cores and

how much memory each job requires. For example, a user on a Slurm

cluster can request that their run_my_rscript.sh script gets to run

with 48 CPU cores and 256 GiB of RAM by submitting it to the scheduler

as:

sbatch --cpus-per-task=48 --mem=256G run_my_rscript.sh

The scheduler keeps track of all running and queued jobs, and when enough compute slots are freed up, it will launch the next job in the queue, giving it the compute resources it requested. This is a very convenient and efficient way to batch process a large amount of analyses coming from many users.

However, just like with a shared server, it is important that the

software tools running this way respect the compute resources that the

job scheduler allotted to the job. The detectCores() function does

not know about job schedulers - all it does is return the number of

CPU cores on the current machine regardless of how many cores the job

has been allotted by the scheduler. So, if your R package uses

detectCores() cores by default, then it will overuse the CPUs and

slow things down for everyone running on the same compute node.

Again, when this happens, it often slows everything done and triggers

lots of wasted user and admin efforts spent on troubleshooting and

communication back and forth.

Shameless advertisement for the parallelly package: In

contrast, parallelly::availableCores() respects the number of CPU

slots that the job scheduler has given to the job. It recognizes

environment variables set by our most common HPC schedulers, including

Fujitsu Technical Computing Suite (PJM), Grid Engine (SGE), Load

Sharing Facility (LSF), PBS/Torque, and Simple Linux Utility for

Resource Management (Slurm).

4d. Running R via CGroups on in a Linux container

This far, we have been concerned about the overuse of the CPU cores

affecting other processes and other users running on the same machine.

Some systems are configured to protect against misbehaving software

from affecting other users. In Linux, this can be done with so-called

control groups (“cgroups”), where a process gets allotted a certain

amount of CPU cores. If the process uses too many parallel workers,

they cannot break out from the sandbox set up by cgroups. From the

outside, it will look like the process uses its maximum amount of

allocated CPU cores. Some HPC job schedulers have this feature

enabled, but not all of them. You find the same feature for Linux

containers, e.g. we can limit the number of CPU cores, or throttle the

CPU load, using command-line options when you launch a Docker

container, e.g. docker run --cpuset-cpus=0-2,8 … or docker run

--cpu=3.4 ….

So, if you are a user on a system where compute resources are compartmentalized this way, you run a much lower risk for wreaking havoc on a shared system. That is good news, but if you run too many parallel workers, that is, try to use more cores than available to you, then you will clog up your own analysis. The behavior would be the same as if you request 96 parallel workers on your local eight-core notebook (the scenario in the left panel of Figure 1), with the exception that you will not overheat the computer.

The problem with detectCores() is that it returns the number of CPU

cores on the hardware, regardless of the cgroups settings. So, if

your R process is limited to eight cores by cgroups, and you use

ncores = detectCores() on a 96-core machine, you will end up running

96 parallel workers fighting for the resources on eight cores. A

real-world example of this happens for those of you who have a free

account on RStudio Cloud. In that case, you are given only a single

CPU core to run your R code on, but the underlying machine typically

has 16 cores. If you use detectCores() there, you will end up

creating 16 parallel workers, running on the same CPU core, which is a

very ineffecient way to run the code.

Shameless advertisement for the parallelly package: In

contrast to detectCores(), parallelly::availableCores() respects

cgroups, and will return eight cores instead of 96 in the above

example, and a single core on a free RStudio Cloud account.

My opinionated recommendation

As developers, I think we should at least be aware of these problems, and acknowledge that they exist and they are indeed real problem that people run into “out there”. We should also accept that we cannot predict on what type of compute environment our R code will run on. Unfortunately, I don’t have a magic solution that addresses all the problems reported here. That said, I think the best we can do is to be conservative and don’t make hard-coded decisions on parallelization in our R packages and R scripts.

Because of this, I argue that the safest is to design your R package

to run sequentially by default (e.g. ncores = 1L), and leave it to

the user to decide on the number of parallel workers to use.

The second-best alternative that I can come up with, is to replace

detectCores() with availableCores(), e.g. ncores =

parallelly::availableCores(). It is designed to respect common

system and R settings that control the number of allowed CPU cores.

It also respects R options and environment variables commonly used to

limit CPU usage, including those set by our most common HPC job

schedulers. In addition, it is possible to control the fallback

behavior so that it uses only a few cores when nothing else being set.

For example, if the environment variable

R_PARALLELLY_AVAILABLECORES_FALLBACK is set to 2, then

availableCores() returns two cores by default, unless other settings

allowing more are available. A conservative systems administrator may

want to set export R_PARALLELLY_AVAILABLECORES_FALLBACK=1 in

/etc/profile.d/single-core-by-default.sh. To see other benefits

from using availableCores(), see

https://parallelly.futureverse.org.

Believe it or not, there’s actually more to be said on this topic, but I think this is already more than a mouthful, so I will save that for another blog post. If you made it this far, I applaud you and I thank you for your interest. If you agree, or disagree, or have additional thoughts around this, please feel free to reach out on the Future Discussions Forum.

Over and out,

Henrik

1 Searching code on GitHub, requires you to log in to GitHub.

UPDATE 2022-12-06: Alex Chubaty pointed out another problem, where

detectCores() can be too large on modern machines, e.g. machines

with 128 or 192 CPU cores. I’ve added Section ‘Issue 3: detectCores()

may return too many cores’ explaining and addressing this problem.

UPDATE 2022-12-11: Mention upcoming

parallelly::availableCores(constraints = "connections").